Nine theses on supply chain resilience and its costs

Prof. Dr. Andreas Kemmner and Dirk Ungerechts

If you are involved in inventory management, supply chain planning or S&OP, you are constantly faced with the challenge of designing and managing supply chains that are both efficient and economical in uncertain times.

Since the coronavirus pandemic, the concept of supply chain resilience has come to the fore. Resilience is often understood as the opposite of efficiency – as additional protection against disruptions, bottlenecks and failures. In practice, however, it is clear that resilience cannot simply be ‘created’ without deeply intervening in cost structures, inventories and control logic.

Especially in the context of inventory management and supply chain planning, resilience is therefore less a question of maximum security and more a challenging economic optimisation task. The following nine theses are based on experience from our consulting practice and are intended to contribute to a factual assessment of resilience and its costs.

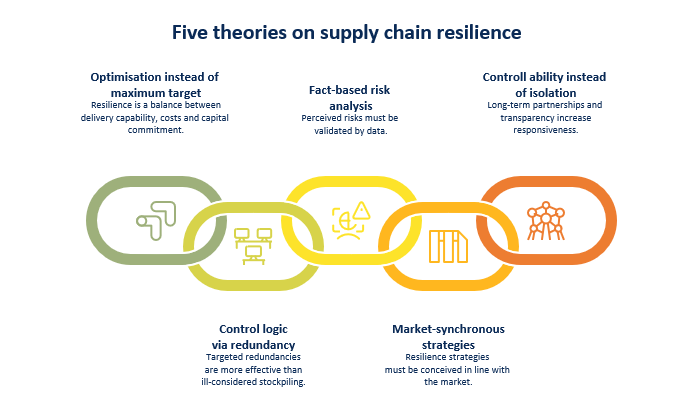

Five theses on supply chain resilience

Resilience is not a maximum goal, but an optimisation task

It is not maximum resilience, but economically sensible resilience that determines competitiveness. The goal is not reliability at any price, but the optimal balance between delivery capability, costs and capital commitment. Overly resilient supply chains are often just as problematic as undersupplied ones.

Redundancy is no substitute for control logic

Dual sourcing or additional safety stocks initially increase complexity and costs. However, without a differentiated risk and cost assessment, the resilience effect remains limited. The decisive factor is not the number of alternative options, but the targeted placement of redundancies at truly critical points.

Perceived risks are often higher than the actual vulnerability of the supply chain

Many resilience decisions are based on strongly influenced crisis scenarios rather than reliable data. A fact-based analysis of delivery performance, bottleneck frequency, recovery times and actual damage levels is a prerequisite for effective and economical measures.

Market-wide crises put the competitive disadvantage of individual failures into perspective.

When entire markets or regions are affected, individual companies rarely suffer an isolated competitive disadvantage. Resilience strategies must therefore be designed in line with market conditions. In such situations, a purely internal company perspective is insufficient.

Resilience comes from controllability, not isolation

Long-term partnerships, transparency along the value chain and coordinated processes increase responsiveness more sustainably than pure regional relocation or national solo efforts. Controllability does not replace risks, but it does make them more manageable.

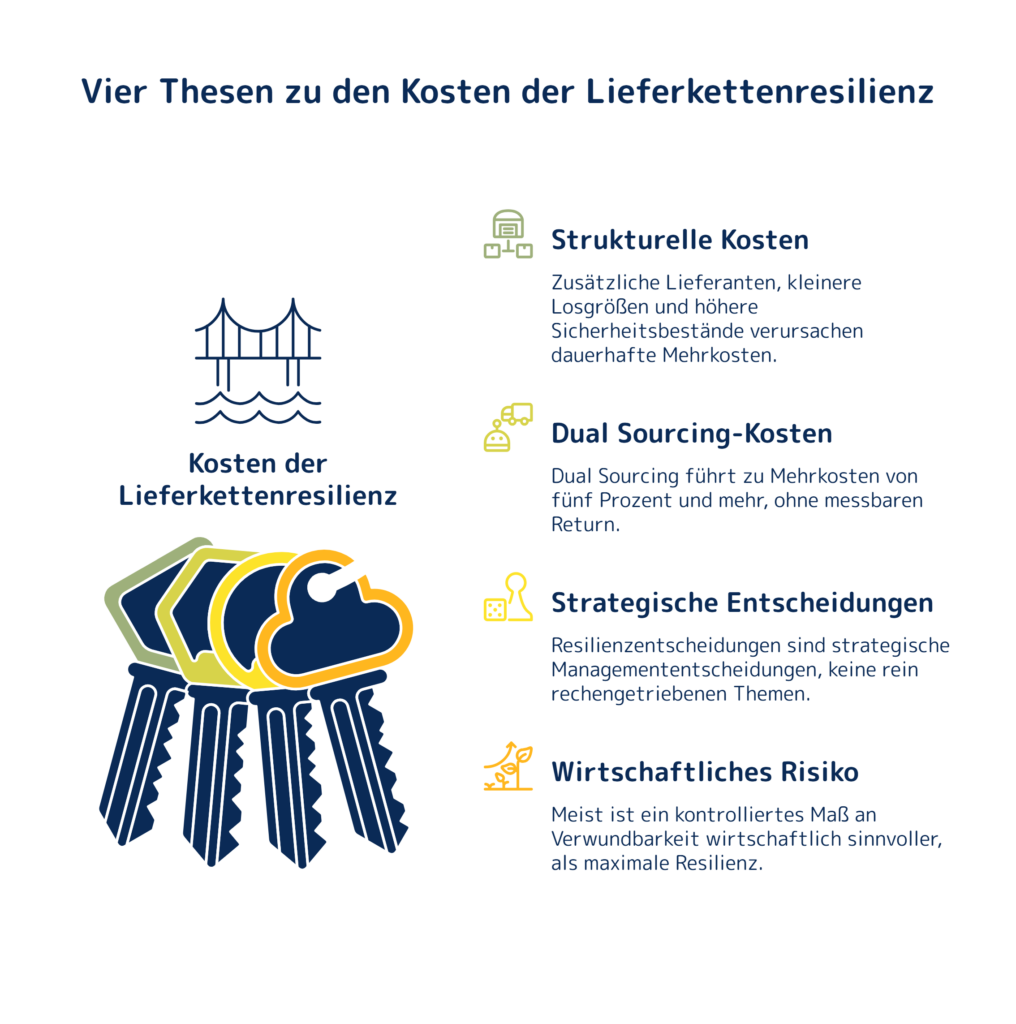

Four theories on the costs of resilience

Resilience comes at a price – and that price is structural.

Additional suppliers, smaller batch sizes or higher safety stocks cause permanent additional costs. These arise regardless of whether disruptions actually occur, for example due to lost economies of scale, higher purchase prices or increasing capital commitment.

Dual sourcing is not a sure-fire recipe for profitability

In many industries, dual sourcing leads to additional costs of five per cent or more without delivering a measurable return. Resilience measures must therefore be clearly prioritised and economically justified rather than introduced across the board.

Resilience is rarely a classic business case

The avoidance of potential failures can only be quantified in monetary terms to a limited extent. Probabilities of occurrence, amounts of damage and market effects are often uncertain. Resilience decisions are therefore strategic management decisions and not purely calculation-driven purchasing or controlling issues. The entrepreneurial responsibility for this lies with the management. It cannot simply be delegated to the supply chain management level.

Greater resilience often comes at the expense of profitability

Companies that prioritise resilience over short-term profitability often do so in order to secure market share in bottleneck situations or to retain customers in the long term. For the majority of companies, however, a controlled level of vulnerability makes more economic sense.

In summary, we view resilience as a management issue rather than purely a security issue.

Future-proof supply chains are not created through maximum security, but through transparency, clear decision-making logic and adaptive management models. Resilience is therefore not an add-on to the existing supply chain, but an integral part of its management.